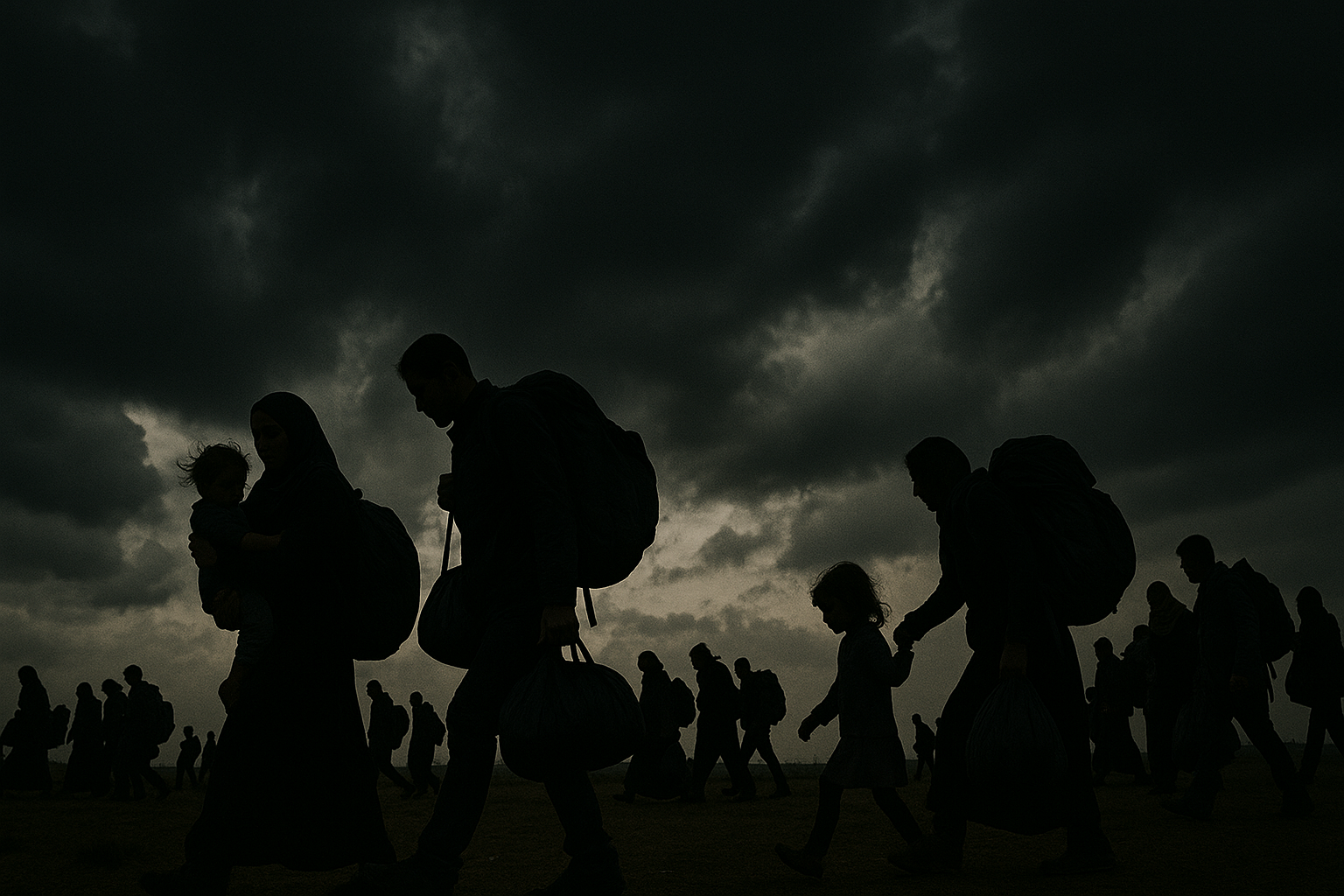

Exile was meant to be an escape. For thousands of Uyghurs who fled Xinjiang’s iron web, freedom lay across borders — in democracies that promised safety, dignity, and the right to speak. But exile has not meant peace. China’s persecution does not stop at its borders; it has gone global.

From malware to manipulation, from hostage diplomacy to Interpol notices, Beijing has turned the world into an extension of its surveillance state. What began as repression in Xinjiang has become a campaign of transnational intimidation — one that hunts the exiled, silences the outspoken, and punishes the families they left behind.

Cyber Shadows

The internet, once the Uyghur diaspora’s refuge, is now its battlefield. According to the Uyghur Human Rights Project’s 2021 report Your Family Will Suffer, Beijing’s global intimidation campaign has targeted Uyghurs across 22 countries since 2002 — escalating sharply after the mass internment drive of 2017. Researchers recorded over 5,500 cases of digital harassment, hacking, and surveillance aimed at silencing dissent abroad.

In interviews with Uyghurs across North America, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific, nearly 96 per cent reported feeling digitally unsafe; three-quarters had experienced direct cyberattacks or monitoring.

Chinese intelligence agencies have developed at least four sophisticated malware families — SilkBean, DoubleAgent, CarbonSteal, and GoldenEagle — embedded within fake Uyghur-language keyboards, religious apps, and news sites. These tools enable full-device takeover, microphone activation, message exfiltration, and GPS tracking. Cybersecurity firm Lookout traced the infrastructure of these attacks directly to Beijing.

For activists like Nurgul Sawut in Australia, the threat became personal. Her Facebook was flooded with fake accounts spreading smears and malware; soon after, her family in Xinjiang disappeared. Weeks later, Chinese state media labelled her a “terror suspect.” The message was unmistakable: speak out, and your family pays the price.

Families as Hostages

Beijing’s most effective weapon is emotional blackmail. Uyghurs abroad receive phone calls from relatives in Xinjiang — voices trembling, words monitored, officials listening in. The calls begin politely and end with threats. “Your family will suffer,” security agents warn.

In Japan, a man named Yusup was contacted by a Public Security Bureau officer through WeChat. He was ordered to gather intelligence on fellow exiles. When he refused, his parents vanished. The officer then offered a bargain: if Yusup wrote pro-China posts online, his family might be spared. The transaction was emotional extortion disguised as patriotism.

In Washington, Uyghur activist Rushan Abbas delivered a speech on China’s camps in 2018. Six days later, her sister Gulshan was arrested and sentenced to 20 years in prison on fabricated terrorism charges.

Across Europe, Uyghurs report calls made under duress — family members forced to plead for silence while Chinese officials hover nearby. In the Netherlands, activist Abdurehim Gheni received threats during protests; in Belgium, police had to intervene after men shadowed Uyghur gatherings.

This is Beijing’s hostage diplomacy on a human scale: punishing one body to control another.

Weaponising Interpol

China’s repression extends into the institutions meant to enforce global justice. For years, Beijing exploited Interpol Red Notices — international alerts typically reserved for criminals — to target political dissidents. Dolkun Isa, president of the World Uyghur Congress, lived under one such notice for over a decade. Issued at Beijing’s request on vague charges, it restricted his travel, froze bank accounts, and shadowed him across airports.

Though Interpol eventually removed the notice in 2018, Isa’s case exposed how authoritarian states can manipulate multilateral systems for persecution. Chinese officials now issue Red Notices disguised as financial crimes to avoid scrutiny. As Ted Bromund of the Heritage Foundation put it, “They use Red Notices like a pin through a butterfly — immobilising exiles without ever touching them.”

The practice continues. Uyghurs remain vulnerable to detention in third countries that fear Beijing’s wrath, revealing how international policing can be twisted into an instrument of fear.

The Long Arm of Retaliation

Even as evidence mounts, Beijing’s retaliation has become institutional. After the United States imposed Global Magnitsky sanctions in July 2020 on senior Xinjiang officials — including Chen Quanguo, the region’s Party Secretary — China struck back. It sanctioned European lawmakers, British MPs, and academics who had criticised its policies.

A year later, coordinated action by the US, EU, UK, and Canada sanctioned four more Chinese officials — Chen Mingguo, Wang Junzheng, Wang Mingshan, and Zhu Hailun — for systematic abuses. Yet even these steps were limited. Chen Quanguo, widely considered the chief architect of Xinjiang’s internment system, was conspicuously absent from the EU’s sanctions list — an omission widely interpreted as a sign of political caution.

Freedom House estimates that China now conducts the world’s most sophisticated campaign of transnational repression, affecting activists in at least 43 countries between 2014 and 2024.

For exiled Uyghurs, this means no place feels fully safe. Some stop attending protests, fearing reprisals; others withdraw from activism altogether, haunted by the knowledge that every public act risks private catastrophe for loved ones back home.

The Failure of Refuge

The world’s democracies, despite rhetoric, have struggled to protect those fleeing persecution. In interviews, only 44 per cent of Uyghur exiles said they believed host governments took threats seriously; barely one in five felt their cases would ever be resolved.

In 2021, Dutch authorities were found to have shared personal information of Uyghur activists with Beijing under the guise of “visa verification,” inadvertently facilitating family harassment. In Turkey, dozens of Uyghurs were detained pending deportation at China’s request before international pressure forced Ankara to relent.

Even liberal democracies often lack cyber-defence frameworks robust enough to confront Beijing’s digital espionage. Only a third of Uyghur exiles surveyed said they knew whom to contact for cybersecurity help, even as 90 per cent expressed the desire to learn.

Exile, once a symbol of freedom, has become another layer of struggle — a life lived under watchful silence.

Digital Colonisation and the Myth of Sovereignty

China’s capacity to project repression globally represents a new form of digital colonisation. Through surveillance technologies, spyware, and online disinformation, Beijing has effectively extended its censorship model across borders.

This campaign erodes sovereignty not only of victims but of host nations themselves. Democracies that tolerate such intimidation within their borders risk normalising authoritarian influence under the veneer of diplomacy and trade.

Uyghur exiles now describe their experience as living in “invisible exile” — physically free yet psychologically bound. The state they escaped continues to shape their speech, their relationships, even their silences.

Resisting the Reach

Despite fear, the diaspora endures. In Washington, the World Uyghur Congress and Campaign for Uyghurs have become vital voices documenting atrocities and lobbying for accountability. Activists coordinate across continents, from Munich to Melbourne, using encrypted communication and grassroots networks to sustain their cause.

The same digital tools that Beijing weaponises for control are being reclaimed for resistance. Online archives preserve banned Uyghur literature; social media amplifies survivor testimonies. The struggle for truth now plays out on the same screens that carry spyware — a contest between suppression and survival fought byte by byte.

The World’s Responsibility

China’s transnational repression demands more than sympathy — it requires systemic response. Western governments must expand Magnitsky sanctions to include technology suppliers complicit in digital surveillance, strengthen refugee protections, and support diaspora cybersecurity initiatives.

Above all, international law must adapt. When authoritarian regimes export repression through technology, traditional notions of borders, asylum, and sovereignty are no longer adequate. Without new norms of accountability, the global commons risks becoming an authoritarian playground.

Freedom in Defiance

For Uyghurs abroad, survival is defiance. Every protest held, every interview given, every public memory preserved undermines Beijing’s attempt to erase them from history.

They live with the constant knowledge that each word may cost them family — and yet they speak. Their courage, amplified through exile, ensures that China’s crimes are not confined to the silence it seeks to impose.

The shadow may follow, but so does the light of testimony.