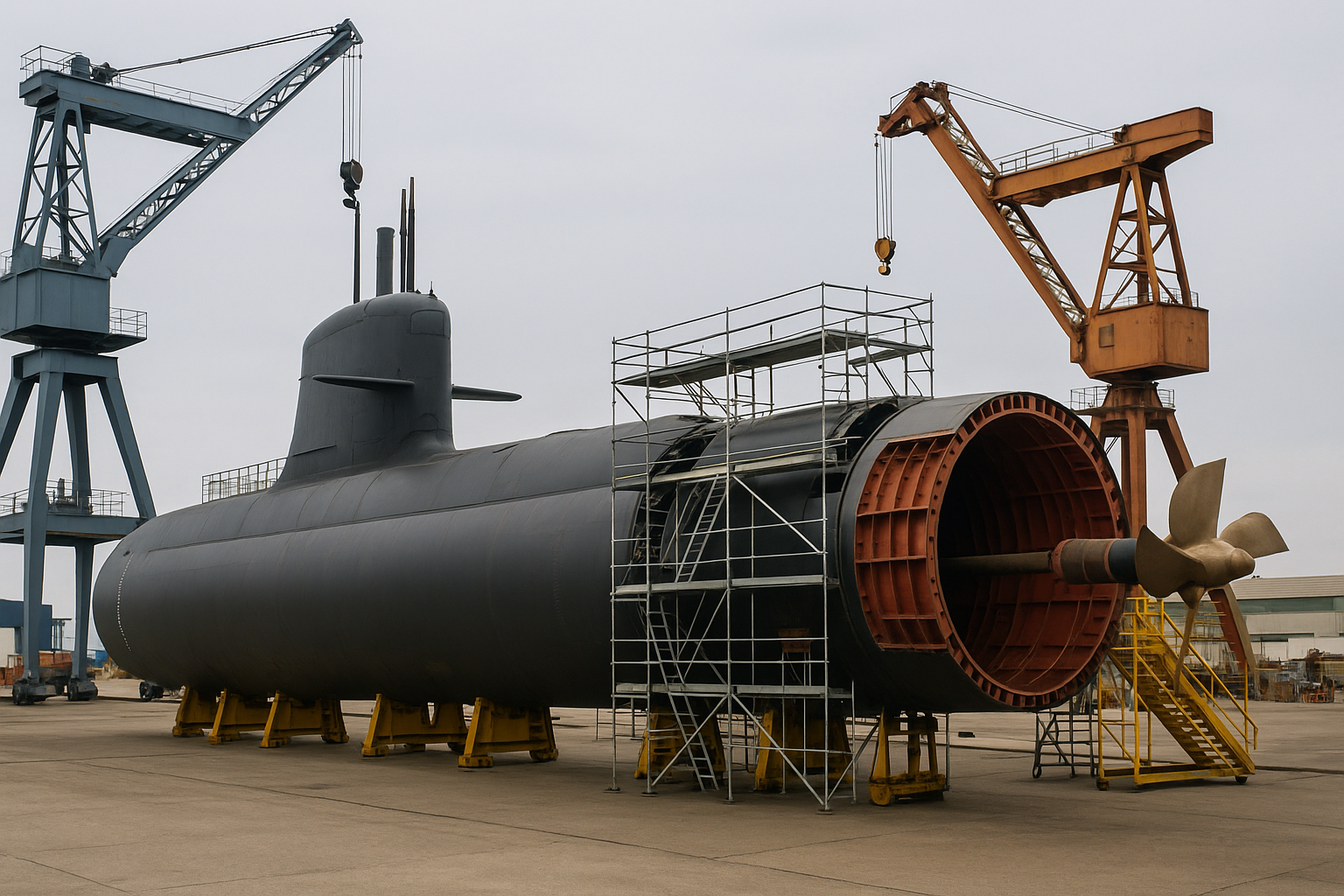

The Pakistan Navy recently formally launched its third Hangor-class submarine, the future PNS Mangro, during a ceremony at the Wuchang Shipbuilding Industry Group’s Shuangliu base in Wuhan, China. The high-profile event was attended by senior naval officials from both Pakistan and China, underscoring the strategic weight of this bilateral defence cooperation.

When the Pakistan Navy launched its first Hangor-class submarine in April 2024, it was considered the start of a new era in the country’s undersea warfare capability. The submarines’ cutting-edge weapon systems and advanced sensors would be pivotal in sustaining a regional balance of power and ensuring long-term maritime stability. The Pakistan Navy expects that the Hangor-class initiative would bring “a fresh dimension to the enduring, time-honoured partnership between Pakistan and China.”

Based on China’s Yuan-class design, the eight-boat programme — four to be built in China and four at Karachi Shipyard — is the largest submarine contract in Pakistan’s history. But, the split construction of Hangor-class submarines between China and Pakistan introduces challenges for the Pakistan Navy, primarily in terms of quality control, integration of systems, and potential delays. While the submarines offer advanced capabilities like air-independent propulsion (AIP), splitting the build could lead to inconsistencies in quality and performance, impacting their operational effectiveness.

Submarines built in different locations, even with the same design, can have subtle variations in construction and component quality due to differing standards and quality control procedures at the Chinese and Pakistani shipyards. If quality control is not rigorously enforced at both locations, it could result in defects or inconsistencies in critical systems, potentially affecting the submarine’s performance, reliability, and safety.

Integrating components and systems built in separate locations can be complex. It may lead to compatibility issues, requiring extra effort and resources to ensure seamless operation. The Combat Management System (CMS), a crucial component, has faced delays due to integration issues and potential incompatibilities with existing Pakistani naval systems. Additionally, the initial plan to use German MTU engines was scrapped due to export restrictions, forcing a switch to Chinese CHD620 engines, which introduces uncertainties about performance and reliability.

Submarines with components from different sources may require specialised maintenance procedures and spare parts, potentially increasing the complexity and cost of maintenance for the Pakistan Navy. Inconsistencies in components or systems could affect the interoperability of the submarines with other naval assets, potentially limiting their effectiveness in joint operations.

The split construction model can introduce delays in the delivery of submarines if there are issues with quality control or integration, potentially impacting the Pakistan Navy’s modernisation plans. Reports of malfunctions in other Chinese-supplied naval assets, along with concerns about after-sales support, have fuelled scepticism about the reliability of Chinese-origin systems, complicating matters for the Pakistan Navy.

A split construction model can increase Pakistan’s dependence on China for maintenance and upgrades, potentially limiting the Pakistan Navy’s autonomy. The Hangor project is seen as part of China’s broader efforts to strengthen its influence in the Indian Ocean region. In fact, the submarine programme is part of a wider pattern of Chinese support to Pakistan’s defence sector. In recent years, Pakistan has inducted Chinese-built JF-17 fighter aircraft, HQ-9/P long-range air defence systems, and, most recently, Z-10ME attack helicopters. Pakistan now has 81% of its defence systems supplied by China.

This heavy reliance on Chinese defence exports also poses risks for Pakistan. It has made the country’s defence procurement somewhat one-dimensional, limiting its ability to diversify its military capabilities. The political alignment between Pakistan and China, often referred to as an “all-weather friendship”, ensures a stable supply chain but also exposes Pakistan to geopolitical risks, especially given China’s growing assertiveness in regional affairs.

In conclusion, the split construction model introduces challenges related to quality control, integration, maintenance, and potential delays. Addressing these challenges through robust quality control measures and close coordination between Chinese and Pakistani shipyards will be crucial for the Pakistan Navy to realise the full potential of these submarines.