In October 1962, while the world’s attention was fixed on the nuclear brinkmanship between Washington and Moscow, another crisis was unfolding in the Himalayas. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) launched a surprise assault across India’s northern frontier, turning a festering border dispute into a full-scale war. For India, it was a military and moral shock; for the global community, it was an early glimpse of Beijing’s willingness to use force while speaking the language of peace.

The 1962 conflict was not a spontaneous border skirmish but a deliberate act that violated the core principles of the United Nations Charter. Article 2(3) requires member states to “settle their international disputes by peaceful means,” while Article 2(4) obliges them to “refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” By invading Indian territory in Ladakh and the North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh), China flouted both. Its actions demonstrated that the PRC’s revolutionary ideology and historical grievances would often outweigh respect for international law.

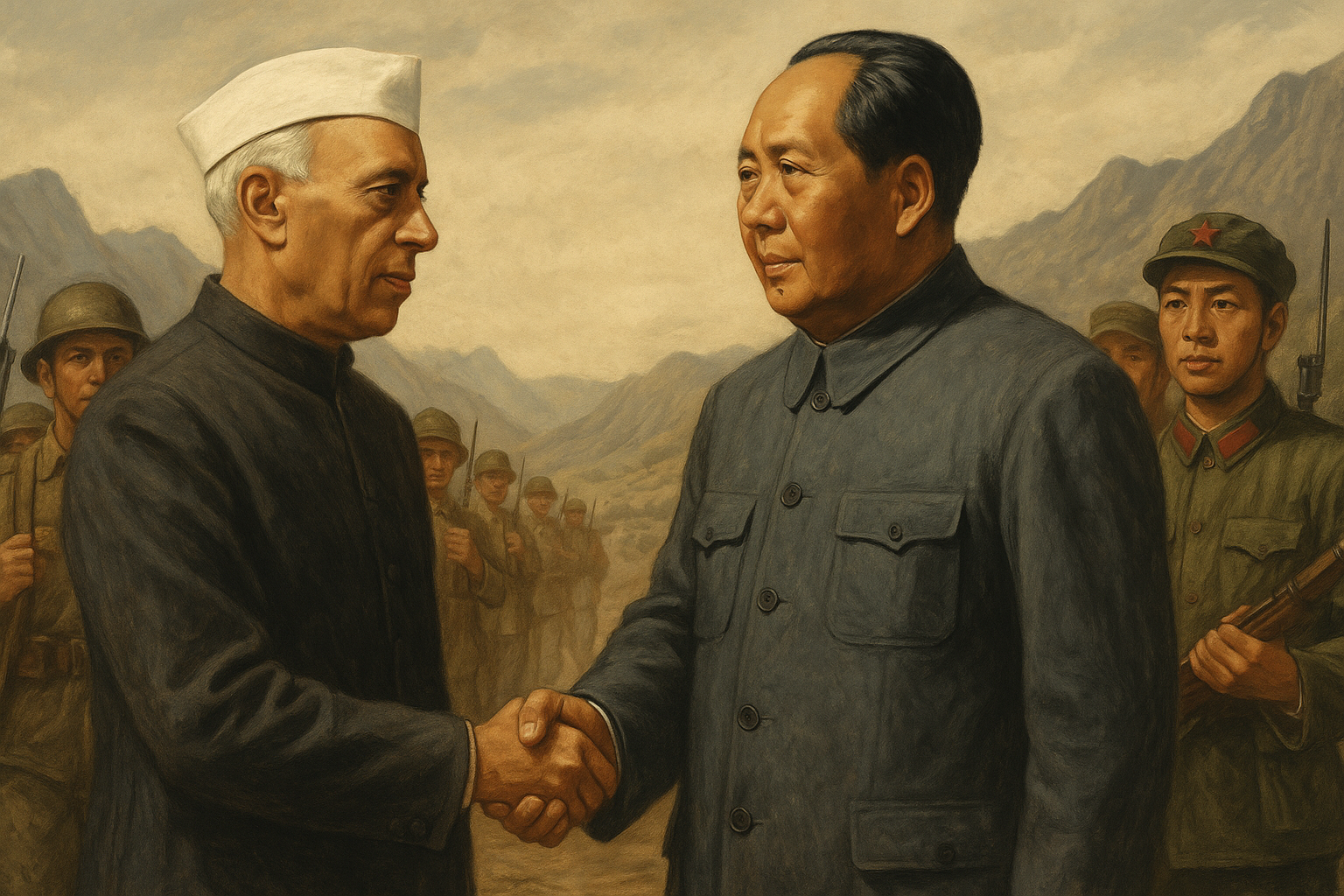

From Panchsheel to Betrayal

Only eight years earlier, India and China had signed the Panchsheel Agreement — the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence — which were supposed to anchor their post-colonial relationship in mutual respect, non-aggression, and equality. New Delhi’s recognition of Chinese sovereignty over Tibet was a major diplomatic concession, reflecting Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s faith in Asian solidarity and his hope that shared anti-imperialist sentiment could overcome territorial disputes.

Beijing saw things differently. The Communist leadership regarded international law as an instrument of Western hegemony and approached agreements through the prism of tactical utility. The ink on Panchsheel was barely dry when Chinese troops began probing Indian positions in Barahoti, Longju, and Aksai Chin. By 1959, the PLA had constructed a road through Aksai Chin — an area India considered its own — while the brutal suppression of the Tibetan uprising and the Dalai Lama’s flight to India hardened mutual suspicion.

When Mao Zedong approved “self-defensive counter-attacks” in 1962, he did so after years of diplomatic engagement that had masked military preparation. The offensive’s twin thrusts — in the western sector of Ladakh and across the McMahon Line in the east — were designed to achieve swift territorial gains and to shatter the notion of peaceful coexistence that Nehru had championed.

A War Beyond the Mountains

The fighting lasted barely a month. On October 20, 1962, the PLA launched coordinated attacks along a thousand-kilometre front, overwhelming poorly equipped Indian forces unprepared for high-altitude warfare. By the time Beijing declared a unilateral cease-fire on November 21, it had withdrawn in the east but retained control of Aksai Chin — territory it occupies to this day.

For China, the operation achieved several goals at once. It humiliated India, secured a strategic corridor linking Tibet to Xinjiang, and signalled to the wider world that the newly assertive PRC would not be bound by norms written by others. The decision to strike while the United States and the Soviet Union were absorbed by the Cuban Missile Crisis underscored the opportunism of Chinese strategy — exploiting distraction and ambiguity to consolidate gains.

The United Nations and the Limits of Principle

India appealed to the international community, invoking the very principles that China had breached. Yet the response was muted. The United Nations did not condemn Beijing’s aggression, largely because of the peculiar geopolitics of the era. In 1962, the PRC was not a UN member; the Republic of China (Taiwan) still held China’s seat. Any resolution censuring Beijing would have entangled the organisation in the question of Chinese representation — a debate most member states wished to avoid amid superpower tensions.

Cold War calculations also played a part. Washington was consumed by the standoff in Cuba and reluctant to open another front in Asia. Moscow, preoccupied with averting nuclear confrontation, adopted a posture of neutrality despite its growing partnership with India. The combination of these factors left New Delhi diplomatically isolated at the very moment it needed international support.

A Pattern Emerges

The 1962 war exposed not only India’s military unpreparedness but also a deeper truth about China’s approach to international relations. Agreements, whether multilateral or bilateral, were tools to be used — and discarded — in pursuit of strategic advantage. The principles of the UN Charter and Panchsheel, meant to prevent precisely such conflicts, became collateral damage in Beijing’s quest to rewrite its borders and its history.

That lesson would echo through the decades. From the 1993 and 1996 border agreements to the Border Defence Cooperation Agreement of 2013, China has repeatedly pledged peace while creating conditions for confrontation. The behaviour pattern that began with the assault of 1962 resurfaced in the Galwan Valley nearly sixty years later, revealing a continuity that India can no longer afford to overlook.

The Unheeded Warning

The 1962 invasion was more than a military campaign; it was an early test of the post-war international order’s capacity to enforce its own rules. The failure to hold China accountable normalised selective adherence to the UN Charter and encouraged a revisionist power to expand its ambitions under the cloak of victimhood.

For India, the lesson was harsh but enduring: peace with China cannot rest on declarations or signatures alone. It must be underwritten by preparedness, deterrence, and a clear-eyed understanding that Beijing’s diplomacy often begins where its deception ends.