I have lived many lives inside one body. I was a child soldier, a spy, a prisoner, an informant, and at times a ghost moving between two worlds—Tamil and Sinhalese, enemy and ally, victim and accomplice. But of all the shadows that haunt me, none is as heavy as the one buried beneath the soil of Chemmani in Jaffna. Between 1995 and 1997, I stood close enough to smell the stench of bodies rotting in the ground, close enough to see the boots of soldiers pressing down the earth after digging shallow graves. I was there with the Sri Lankan military when they turned Chemmani into a graveyard of the disappeared.

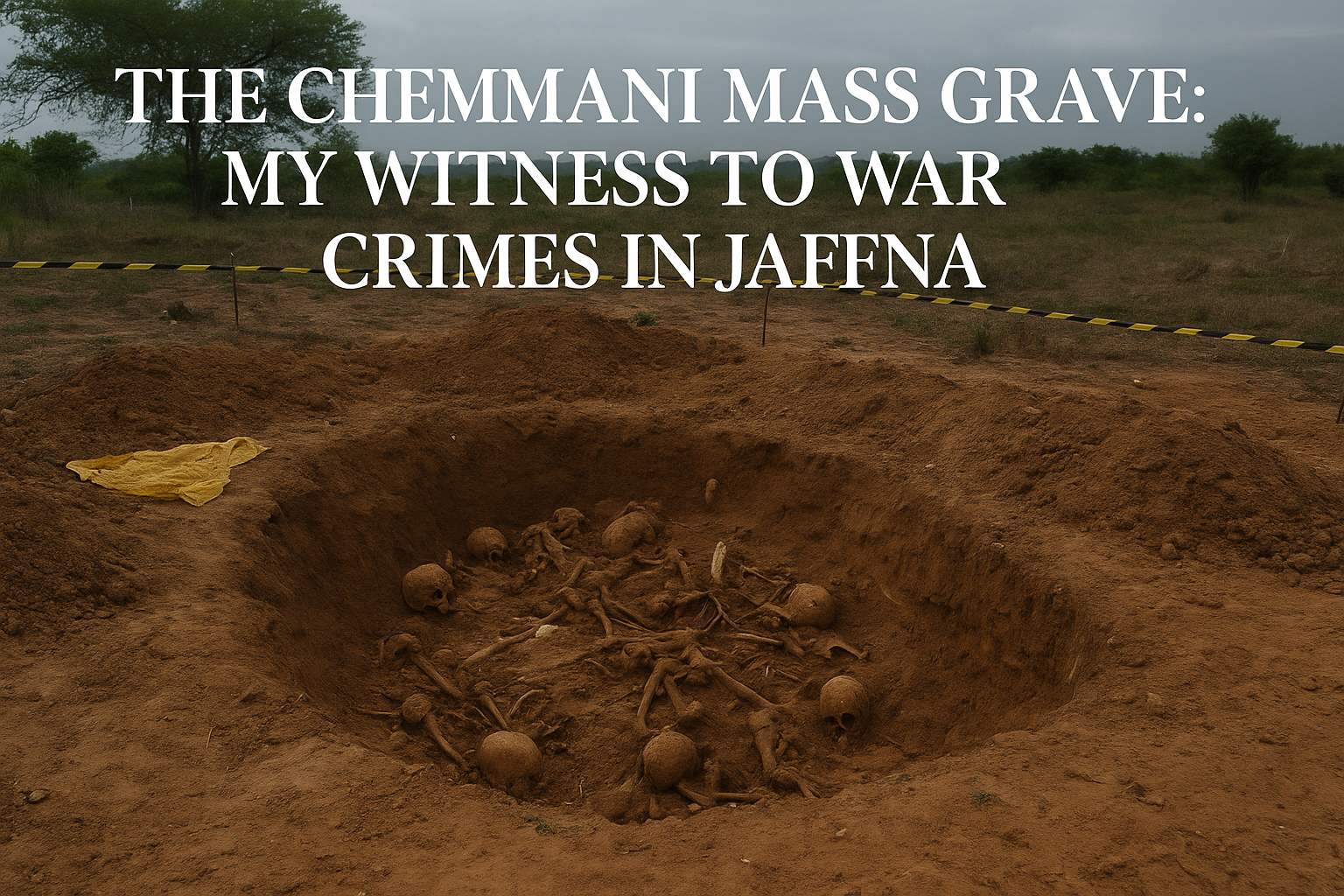

What later surfaced in the newspapers—141 skeletons pulled out of the dirt, tiny shoes and toys recovered beside baby bones—was not a surprise to me. I had already seen the ground swallow the people. I had already heard the cries muffled by gunfire, the last screams of young boys and girls who were accused of being Tigers, sometimes with no evidence at all. To me, Chemmani was not just a crime scene; it was a landscape of memory, one I carried inside me long before it was excavated.

When Operation Riviresa began in late 1995, the Sri Lankan army swept into Jaffna with overwhelming force. I was with them, not as a free man but as an asset, a double agent whose life hung by a thread. By then I had already betrayed the Tigers and confessed to the Research and Analysis Wing of India, only to be turned over to the Sri Lankan Directorate of Military Intelligence. They called me “05,” a code name, a number. Numbers are useful in war. They strip away the burden of names, of humanity. Numbers are easier to kill.

Jaffna fell under military control, but victory came with suspicion. Every Tamil youth was a potential Tiger. Every girl walking alone might be a Black Tiger suicide bomber. Every boy on a bicycle might be carrying intelligence. The paranoia of the soldiers was endless, and it created a system of arrests, disappearances, and killings that spiraled into atrocity.

I was assigned to identify suspects—spotters, they called us. We pointed out who looked like a Tiger, who had the wrong walk, who had eyes that lingered too long on a checkpoint. Many of the people I pointed at never came back. Some were Tigers. Many were not. Some were my classmates, neighbors, even relatives of relatives. I told myself I had no choice. When I refused, the army tortured me and threatened to go after my family. Survival meant complicity. Survival meant silence. But silence does not erase memory.

The disappearances began quietly. Youths taken at checkpoints, blindfolded, shoved into jeeps. Mothers ran from camp to camp, begging for news, clutching photographs of their sons and daughters. The officers brushed them off or laughed in their faces. Some women tried to follow the jeeps, screaming until soldiers struck them with rifle butts.

I remember one boy clearly—Sivapalan, only nineteen, thin and timid. He had been accused of ferrying supplies for the LTTE, though no evidence was shown. I saw him dragged into Ariyalai camp. He begged in Tamil, “I am not a Tiger, I swear.” He never came out. Days later, I was sent with two soldiers to Chemmani. They told me to watch. They made me hold a torch while they dug a shallow pit. Then they brought Sivapalan, his hands tied, face bruised. He cried for his mother. A shot rang out. His body convulsed, then lay still. They kicked him into the pit, poured sand and lime, and patted the soil flat with their boots. I stared into the darkness, my stomach twisting, bile rising in my throat. The soldiers joked that night about “planting seeds.” I could not laugh. I could not speak.

Chemmani was not an official cemetery. It was wasteland, scrubby ground near the road, half-hidden from the town. The military had easy access. It became routine: prisoners taken from Ariyalai, Kankesanthurai, and other camps would end up in Chemmani. Some were executed on the spot. Others were tortured first. I saw pits holding three, four, sometimes five bodies crammed together, limbs twisted unnaturally. They were buried only a meter or two deep, not to honor them but to dispose of them quickly.

In those days, the air at Chemmani was foul. The smell of decay lingered in the heat. Dogs prowled at the edges. The soil was uneven, marked by patches of freshly turned earth. Every time I passed, I could feel the land breathing under me, restless with the weight of the dead.

The soldiers carried out their orders without hesitation. Some were cruel, some indifferent, some even guilty but powerless. One officer confided to me that orders came from high command to “clear the peninsula” of suspected Tigers. Chemmani was part of that order. He said, “If we don’t bury them here, they’ll rise again as martyrs.” He believed he was fighting ghosts.

In 1996, the rape and murder of a schoolgirl, Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, shattered the silence. She was stopped at a checkpoint on her way home from school, raped by soldiers, and killed. When her mother, brother, and neighbor went to look for her, they too were killed. The crime could not be hidden. International pressure mounted. A soldier, Somaratne Rajapakse, confessed not only to the murders but also to the existence of mass graves in Chemmani.

When I heard Rajapakse speak, my blood ran cold. Everything he said confirmed what I had already seen. The graves were real. The bodies were there. But to hear it spoken aloud was like tearing away a bandage from a wound I had tried to keep covered.

By 1997, I had witnessed dozens of burials. Sometimes I was forced to assist, holding lamps, digging, even carrying bodies. I never pulled the trigger, but my silence made me complicit. Each body I saw lowered into the ground felt like a stone placed on my chest.

The soldiers grew careless. They buried children, women, and old men along with suspected cadres. I remember a young mother with her infant. The baby’s bottle rolled out of her bag into the dirt as they dragged her body. One soldier kicked it aside. I can still hear the rattle of that plastic bottle against the stones. Years later, when excavations began and artifacts like baby bottles and toys were found, I knew they were the same items I had once seen tossed into the dirt.

I tried to tell myself I was only a witness, not a perpetrator. But witnessing without action is its own crime. Every day I returned home, washed my face, and looked in the mirror. The man staring back at me was hollow-eyed, haunted, broken. I was twenty-four years old but felt a hundred.

When I later escaped Sri Lanka and began telling my story, many doubted me. Some said I exaggerated, others said I fabricated. But when the excavations in 2025 uncovered 141 skeletons at Chemmani, including the remains of children with schoolbags and toys, I felt vindicated. The earth had spoken. The truth I had carried for decades was no longer just my memory; it was physical evidence pulled from the soil.

But vindication does not erase guilt. I live with the knowledge that I was there, that I did not stop it, that I could not stop it. I live with the nightmares—faces half-buried in sand, eyes wide open, mouths frozen mid-scream. I live with the sound of the soldiers’ laughter, the smell of death, the weight of silence.

In Chapter 25 of my book Spy Tiger: The 05 File, I called it simply “War Crimes in Jaffna.” But those words are inadequate. What happened in Jaffna between 1995 and 1997 was not just war crimes—it was systematic erasure of a people. It was genocide in slow motion. Chemmani was only one site among many. Across the North and East, mass graves dot the landscape, each one a scar in the earth, each one a testimony to lives stolen.

When I stood in Chemmani, I knew I was looking at the dark heart of the war. This was not a battlefield clash between armed combatants. This was the killing of unarmed civilians, executed in secret, denied in public, and buried in silence.

In 2025, when the excavations began at Chemmani and Ariyalai, the world saw what I had already known. Skeletal remains pulled out by the dozens, shallow pits revealing tangled bones, artifacts proving the presence of children. Families gathered at the site, weeping, hoping to identify their loved ones. The smell of soil mixed with tears.

Human rights groups demanded DNA testing, accountability, international oversight. But justice remains slow, obstructed by bureaucracy and politics. For me, each skeleton was a voice rising from the ground, asking why it took so long.

I carry the burden of memory. Some people say memory fades with time. For me, it sharpens. The older I get, the clearer the images become. Perhaps it is because I am no longer afraid to speak. Perhaps it is because the dead demand to be remembered.

I often ask myself: could I have done more? Could I have saved even one life? The answer is complicated. I was a prisoner, a spy, a man under threat. But I was also there, alive, while others died. That fact binds me forever to Chemmani.

I tell this story not for myself but for those who cannot. For the mothers who still wait, for the fathers who still hold faded photographs, for the brothers and sisters who never came home. I speak because silence is what allowed Chemmani to happen. Silence is what allows atrocities to repeat.

To bear witness is painful, but to deny what I saw would be to betray the dead all over again. Chemmani is not only a mass grave in Jaffna—it is a mirror of our humanity, a test of whether we will remember or forget.

Today, when I hear the word Chemmani, I do not think of a place. I think of the faces of the disappeared. I think of Sivapalan crying for his mother. I think of the baby’s bottle rolling in the dirt. I think of the soldiers’ boots pressing down on freshly turned soil.

I have lived many lives, but this chapter will follow me to my grave. Chemmani is inside me. And until the truth is fully acknowledged, until justice is done, I will carry that grave with me wherever I go.